By Jim Delaney, CEO, Traction AI

Two-Part Series for Veteran Founders – Understanding Angels, VCs, Private Equity & Strategic Investors

Introduction — Why This Series Exists

Over the past decade, I’ve had the privilege of working with hundreds of veteran entrepreneurs across programs like PenFed, The MilVet, VetsinTech, FirstWave, service academy entrepreneurial groups, veteran accelerators, pitch programs, and founder cohorts. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned, it’s that the veteran entrepreneurial ecosystem is not defined by a single archetype:

• Some founders are building the next AI-native or cybersecurity company.

• Some are growing reliable, cash-flowing service businesses.

• Some are building professional practices or coaching companies.

• Some are developing deep-tech defense innovations.

• Some are transitioning to build something steady and self-directed.

The diversity is extraordinary — and intentional. But that diversity creates a problem: Veteran entrepreneurs constantly receive fundraising advice that was never meant for them.

Nearly all mainstream content assumes the goal is to build a Silicon Valley-style blitz scaling startup. But veteran businesses fall across a wide spectrum of ambition and maturity. Some need institutional capital. Some don’t. Some should pursue venture funding. Many absolutely shouldn’t. So this series exists for one purpose:

To give veteran founders a clear, honest understanding of how capital works — and how to choose the right kind for the business they are actually building.

Part I — Strategic Understanding (This Article)

This article gives you the map. It breaks down the major types of investors — Angel, Venture Capital, Private Equity, and Strategic — through a veteran-centric lens. It explores:

• Founder intent

• Capital alignment

• Investor psychology

• Second-order effects

• Governance and control

• Exit paths

• Veteran-specific strengths and traps

• Alternative forms of capital

• The Traction AI rule of capital alignment

It’s the strategic foundation every founder should understand before taking a single meeting.

Part II — Operational Readiness (Next Article)

That article gives you the compass. It will present a practical, tactical 12-point diagnostic to determine:

• Whether you’re actually ready for capital

• What kind of capital you qualify for today

• What gaps you must close

• What systems investors will expect

• How to prepare your GTM, metrics, and financials

Think of Part I as the theory of alignment and Part II as the practice of readiness. Together, they become the Veteran Capital Playbook.

Why Capital Alignment Matters More For Veteran Founders

Veterans are exceptionally capable founders. They know how to lead, adapt, solve ambiguous problems, and execute under pressure. But these very strengths can mask the early warning signs of misaligned capital.

Veteran founders often overestimate their ability to “muscle through” misfit capital. Or they underestimate their readiness because military culture teaches them not to self-promote. And because veteran businesses span such a wide economic range, many founders misjudge what kind of capital will help — or hurt — their trajectory.

I once coached a veteran founder who took a large VC check far too early. His company wasn’t ready for the velocity, and he wasn’t ready for the governance. The pressure that followed didn’t just reshape the business; it reshaped him. In his words: “I started building the company they wanted, not the company I believed in.”

Conversely, I’ve worked with veteran founders who needed capital — SBA loans, grants, revenue-based financing — but refused to pursue it because they saw raising money as a sign of weakness, not strategy. They held onto the belief that they should be able to do it alone.

But capital isn’t a character assessment. It’s an alignment question. And alignment requires understanding the three stages of company maturity:

Go to Product → Go to Market → Go to Scale

Each stage demands different leadership behavior, different systems, and different capital partners. Misalignment destroys momentum faster than bad execution. This is why capital alignment matters. It’s not about how much money you raise — it’s about who you become when you do.

Founder Intent: The Missing Foundation

Before any founder thinks about investors, valuations, or dilution, they must answer a deeper question: What do I want this business to become? In my experience, veteran founders generally fall into one of four intent profiles:

Each intent leads to a different capital path. Freedom founders rarely need VC. Impact founders may thrive with strategic investors. Wealth-driven founders must think early about exit paths and cap tables. Transition founders often benefit most from non-dilutive capital (SBA, grants, revenue-based financing). Intent precedes strategy. Strategy precedes capital. Or put simply: capital amplifies founder intent — it does not create it. Once you understand your intent, everything else becomes clearer.

The Four Types of Capital (Veteran-Centric View)

Now we shift into the four primary forms of institutional capital — through the lens of a veteran founder.

1. Angels — Belief Capital

Most founders remember the first person who truly believed in their idea. For many veteran founders, that person is an angel investor — often someone who sees in you the same qualities they once bet on in themselves.

Angel investors aren’t buying spreadsheets. They’re buying you.

They are looking at your character, your judgment, your adaptability, and your ability to move through ambiguity with clarity. Angels understand that early-stage entrepreneurship is messy. They don’t expect perfect signals; they expect intellectual honesty, resilience, and the willingness to iterate.

Angel capital fits best when your company is still forming its identity — when you’re in conversations with early customers, refining the problem, building prototypes, or validating your assumptions. You don’t need a large check. You need belief, feedback, and access.

But belief comes with weight. Veteran founders often feel an emotional debt to early angels and push themselves to “show results” before the business is ready. This can create premature acceleration, messy cap tables, or misaligned expectations if the angel imagines a unicorn outcome while the founder is building a highly profitable lifestyle business.

Still, when aligned well, angel capital can be the most supportive and personally meaningful capital a founder ever receives. Belief is powerful — especially when paired with boundaries.

2. Venture Capital — Speed & Scale Capital

If angels buy belief, VCs buy momentum. Venture capital isn’t about who you are today; it’s about who you could become in three to five years if you had the resources to scale quickly. VCs are looking for signs that your company is emerging from experimentation and beginning to show real patterns: repeatable sales, clear ICP definition, early traction with customers, and a GTM motion that doesn’t rely solely on founder heroics.

I’ve worked with veteran founders who were sure VC funding would be the validation they needed — only to find out that VC introduces a completely different operating system. When you accept VC money, you’re signing up for acceleration. Timelines compress. Targets expand. You’re no longer building at your own pace; you’re pacing a fund’s return cycle.

This can be incredibly powerful. VC networks open doors. VC brands attract talent. VC partnerships unlock distribution. But it can also be unforgiving. Veteran founders are accustomed to discipline and endurance, which sometimes leads them to push through a failing strategy simply because they committed to it. I’ve seen founders stay loyal to a flawed product direction because “the VC believed in it,” even though their gut told them the market was shifting.

Venture capital is rocket fuel. Useful only if the rocket is built to fly. When it fits, it can transform a company. When it doesn’t, it can break a founder.

3. Private Equity — Control Capital

Private equity is a different universe entirely. PE doesn’t invest in early-stage ideas or emerging categories. PE invests in companies that already behave like machines.

They want cash flow, predictability, operational rigor, and expansion levers. In many ways, PE behaves like the high-functioning operations officer of the investment world — they believe in discipline, process, and maximization.

PE fits when your business is stable, profitable, and ready to evolve from “founder-led” to “process-led.” This is particularly relevant for veteran-owned services companies, government contracting firms, logistics operations, or B2B service providers that have hit a ceiling and need structural redesign. But PE capital changes identity. It introduces dashboards, KPIs, reporting cadences, restructuring, and governance.

Veterans often adapt well to structure — but I’ve seen founders struggle with the psychological shift from owning every decision to sharing or ceding control. And some founders feel torn between loyalty to their team and the performance expectations of their new institutional partners. PE is not for businesses still discovering themselves. It’s for businesses ready to transform.

4. Strategic Investors — Strategic Advantage Capital

Strategic investors are not buying your company. They’re buying advantage.

They want technology that strengthens their ecosystem, distribution that expands their reach, market access that accelerates their roadmap, or a product that fits naturally into a future acquisition thesis.

Strategic investors are ideal when your product or service complements a larger platform. For many veteran founders in logistics, defense tech, AI, cyber, or energy, a strategic partnership can unlock scale that would be impossible alone.

But strategic capital must be navigated carefully.

• Sometimes the partnership gives you access.

• Sometimes it boxes you in.

• Sometimes it accelerates growth.

• Sometimes it slows you down with integration cycles.

The biggest risk is exclusivity — one contract clause can eliminate other potential strategic partners or acquirers. Veteran founders, driven by loyalty, sometimes commit too early. Strategics are powerful partners when aligned. They are constraints when they’re not.

Autonomy, Control & Governance

One of the most predictable moments in the veteran founder journey happens the first time institutional capital truly enters the room. It’s not the money that surprises them. It’s the governance.

Veterans are used to hierarchy, but they are also used to being the hierarchy inside their own business. They go from being the commander of their own ship to sharing the wheel, and for many, that shift is disorienting.

The truth is simple: Every dollar has a governance cost.

• Angels usually want high trust and light oversight.

• VCs bring board seats, milestones, and accountability rhythms.

• PE introduces operating cadences, KPIs, dashboards, and often structural change.

• Strategic investors wield influence through product alignment, roadmap expectations, and ecosystem integration.

None of this is inherently negative. Governance can bring clarity, discipline, and focus — things veteran founders often appreciate. I’ve seen founders transform chaotic operations into high-performing systems because their new investors imposed a cadence that finally forced prioritization.

But governance also rewires the emotional experience of running a business. Suddenly, you aren’t just answering to customers and employees; you’re answering to stewards of capital. And if your founding intent was autonomy and independence, that shift can feel like losing altitude.

I once advised a veteran founder who built a thriving $10M business. When he took on PE capital, he went from making every decision himself to having to justify hiring, pricing, vendor choices — even leadership changes. It wasn’t that the PE firm was wrong. It was that he had never asked the most important question:

“Who do I want to become once someone else has a say in this business?”

Governance isn’t just a control structure. Governance is an identity structure. Choosing capital means choosing the future version of yourself that will be required to run the company you are building. If you don’t want that future version, the capital is wrong — no matter the valuation.

Exit Path Alignment

One of the hardest conversations I have with veteran founders usually starts like this:

Founder: “I’m thinking about raising capital.”

Me: “What’s your exit plan?”

Founder: “…I haven’t thought about it yet.”

Veterans are trained to focus on the mission immediately in front of them. But entrepreneurship requires dual altitude thinking: present execution and future direction. Without an exit thesis, founders make capital decisions that feel good now but restrict the business later.

Your exit path — even if it's ten years away — dictates your capital path.

If you’re building a lifestyle business designed to create freedom, SBA loans and bootstrapping are usually your best friends.

If you’re building an AI-driven SaaS platform with meaningful TAM, venture capital may be the right catalytic force.

If you’re building a GovCon or services business with strong cash flow, you’re sitting on an ideal PE roll-up candidate.

Deep tech? You will almost always move through SBIR and strategic partnerships before acquisition.

Defense-facing AI or cyber? Strategics are likely your natural acquirers.

Veterans often try to mix incompatible destinies: raise VC but expect autonomy, pursue SBA debt but want blitz scale growth, sign strategic partnerships but expect full independence. These tensions create the very frustrations founders later blame on investors.

Your capital partner is not just a financial choice; it is a directional choice.

You can’t build a dividend business with venture expectations.

You can’t take on strategically restrictive capital and expect open-market optionality.

You can’t take on low-governance loans and expect to be pushed into scale.

Capital is destiny. Choose the destiny you actually want.

Second-Order Effects of Capital

When founders think about raising money, they picture the next six to twelve months: the hires they can make, the features they can build, the customers they can chase. But investors aren’t thinking about six months. They’re thinking about the next six years. That mismatch creates blind spots.

The real consequences of capital rarely emerge in Year One. They show up in Year Three — when burn has quietly drifted up, when milestones tighten, when optionality narrows, when the cap table becomes rigid, or when the founder starts feeling boxed-in by decisions they willingly made early on.

I once spoke with a veteran founder who said, “The money helped us scale, but it also locked us into a path I wasn’t emotionally ready for.” That’s the part founders underestimate: capital not only changes what the company is capable of — it changes what the company must become. Capital accelerates. Acceleration exposes. Exposure transforms.

Second-order effects don’t mean capital is bad. They mean capital is structural. It shapes your pace, your pressure, your decision freedom, your team composition, your exit options, and even your psychology as a leader. If you aren’t prepared for the second-order effects, you will misinterpret them as failures instead of design features.

Emotional & Psychological Realities

Of all the topics in this article, this is the one veteran founders talk about the least — and struggle with the most. Veterans are taught to be self-reliant, mission-focused, and humble. Asking for resources can feel uncomfortable, even disloyal. Speaking confidently about your business can feel like bragging. Changing plans can feel like giving up. Visible failure can feel like a stain on your name.

And because capital often accelerates visibility — both success and struggle — veterans sometimes avoid raising money simply to avoid being seen. I’ve had founders tell me, “I didn’t raise because I didn’t want to let anyone down,” or “I didn’t pitch because I didn’t feel ready yet,” even though they were far more prepared than the average founder walking into a VC room.

The emotional burden is real:

• The fear of failing publicly

• The guilt of disappointing early believers

• The loyalty to team members who were with you from day one

• The pressure to endure beyond what is healthy

• The discomfort with being the face of the company

But here is the truth every veteran founder must internalize: Funding is not weakness. Funding is force projection. And force projection, used ethically, is leadership.

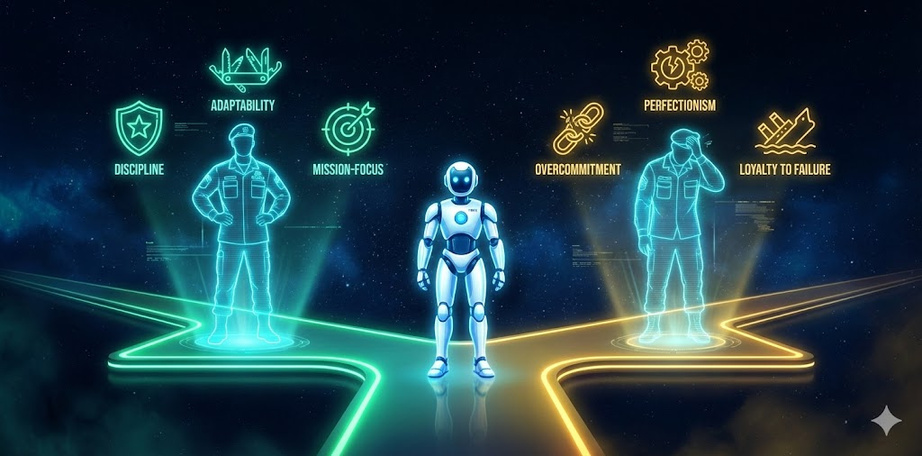

The Veteran Edge & The Veteran Trap

Veterans bring extraordinary strengths to entrepreneurship: discipline, adaptability, integrity, clarity under pressure, mission-driven execution. These become superpowers in every stage of business building.

But every strength has a shadow.

• I’ve seen founders overcommit because they felt they “owed it to the team.”

• I’ve seen founders underprice because they valued service over economics.

• I’ve seen founders refuse help because it felt like burdening others.

• I’ve seen founders stay loyal to broken ideas or failing hires because loyalty felt like duty.

• I’ve seen founders delay GTM motion because perfectionism became a shield.

The edge and the trap are often the same trait in different conditions. Understanding this duality isn’t about fixing flaws. It’s about self-awareness. Capital partnerships don’t just amplify your strengths — they also amplify your traps. If you don’t recognize both, you may choose partners who reinforce the wrong parts of your psychology. To choose the right capital partner, founders must understand both sides of themselves — not just the side they’re proud of.

Alternative Capital Sources

This is the quiet truth almost no one says in the mainstream tech ecosystem: Most veteran businesses should not raise VC or PE — and that’s not a deficiency. It’s alignment. The veteran entrepreneurial landscape is broad. Many of the strongest, most profitable, most durable veteran businesses are built with non-dilutive capital. And unlike many civilian founders, veterans have privileged access to financing paths that reward discipline, planning, and operational rigor.

• SBA loans, especially under the Veterans Advantage program, can power predictable businesses without giving up equity.

• SBIR and STTR grants can fund deep-tech innovation for defense, cyber, AI, and energy — without dilution.

• Revenue-based financing can support early GTM expansion.

• Factoring and lines of credit can stabilize cash flow during scale.

• Veteran-focused angel groups often combine belief with lived experience.

• And bootstrapping — disciplined, profitable, steady growth — is still undefeated.

Some of the best businesses I’ve seen were built from the inside out: disciplined, profitable, steady — not blitz scaled. If you can grow without giving up equity, that’s not just financially smart. It’s strategically mature.

The Traction AI Rule of Capital Alignment

After years of advising founders — especially veterans — I’ve come to see the same pattern repeat itself across industries, maturity stages, and business models: most entrepreneurs don’t fail because they raise too little capital or too much capital. They fail because they raise the wrong type of capital. The consequences:

• Wrong capital creates the wrong expectations.

• Wrong expectations create the wrong behavior.

• Wrong behavior creates organizational drag.

And organizational drag eventually becomes identity-drift — where the founder no longer recognizes the business unfolding in front of them.

I once worked with a veteran founder who raised venture capital to “go faster,” only to discover that the go-to-market motion required more technical maturation and customer education than any VC timeline could tolerate. Another founder raised private equity before stabilizing her operational model, and the new governance cadence overwhelmed her leadership bandwidth almost immediately. And I’ve seen founders sign early strategic deals that blocked future opportunities because the partnership came with invisible handcuffs. These weren’t failures of execution. They were failures of alignment. And that’s why Traction AI teaches a simple but powerful principle: Capital is not fuel – it is structural choice. It determines the company you are building — and the founder you must become.

Every capital type maps to a specific moment in the business lifecycle:

If you are identifying signals, testing hypotheses, and validating belief → you want Angels. Angels amplify your courage, your curiosity, and your early intellectual honesty. They’re there for the formation stage.

If your machine is forming and you are ready to scale a repeatable GTM motion → you want Venture Capital. VCs amplify trajectory, not stability. They push for acceleration, category creation, and velocity.

If your business is stable, profitable, and ready for operational transformation → you want Private Equity. PE amplifies structure, discipline, and systematization. They turn founder-led businesses into high-performance engines.

If your business strengthens a larger ecosystem and you need access to distribution or market power → you want Strategic partners. Strategics amplify reach, legitimacy, and adoption — but often at the cost of optionality.

Founders get in trouble when they borrow alignment frameworks from someone else’s business, someone else’s ambitions, or someone else’s maturity stage. A founder building a $3M/yr consulting practice shouldn’t imitate a founder building a $50M ARR AI platform. A deep-tech innovator shouldn’t imitate a lifestyle entrepreneur. A GovCon firm shouldn’t imitate a consumer brand. They require different capital structures because they are different games. Veteran founders thrive when they recognize that capital doesn’t simply increase resources — it changes the gravitational field of the business. Why?

• Capital is identity.

• Capital is direction.

• Capital is acceleration.

Your job is to ensure it accelerates you along the right path, not the wrong one.

Preparing for Part II

If Part I did its job, you are walking away with something far more valuable than a list of investor types. You now have a language for understanding capital — a way to see the terrain clearly, to decode the incentives of different partners, and to locate yourself along the arc of business maturity. That clarity alone is a competitive advantage. Most founders never develop it. But clarity without readiness is incomplete. And that is where Part II comes in.

Part II will give you The 12-Point Capital Readiness Diagnostic — a structural, practical, unflinching assessment that helps you determine:

• What type of capital you are actually ready for today

• Where your GTM systems fall short of investor expectations

• Whether your financials, metrics, and dashboards support institutional scrutiny

• Whether your governance cadence is mature enough for oversight

• What gaps you must close before raising

• And perhaps most importantly: whether you should raise at all.

Raising capital is not a rite of passage. It is a strategic act of identity construction.

Some founders will emerge from Part II realizing they are ready for investors, partners, and acceleration. Others will realize they can (and should) grow more powerfully through non-dilutive pathways. And still others will realize that capital is not the next milestone — operational maturity is. This is why we created this two-part series. Not to push founders into raising money, but to help them choose their path with intention, clarity, and confidence. Part I gave you the map. Part II gives you the compass.

Together, they form the veteran entrepreneur’s capital playbook — a framework built on alignment, maturity, and the unwavering belief that founders who understand themselves can build companies that endure.

Part II is next.